Look closely… Closer, yet closer!

Axes and daggers

Study the carved bronze age daggers and axes. There’s comprehensive detail on Mike Pitt’s site.

It’s been suggested that they represent sky-gods. In Indo-European convention hatchet heads were frequently connected with tempest gods – and some surviving European fables suggest upright axes are used as supernatural charms to secure harvests, individuals and property against lightning and tempest harm. It should be noted all Stonehenge axes are heads upright and all daggers are downward pointing. Maybe they’re offerings to placate the storm gods.

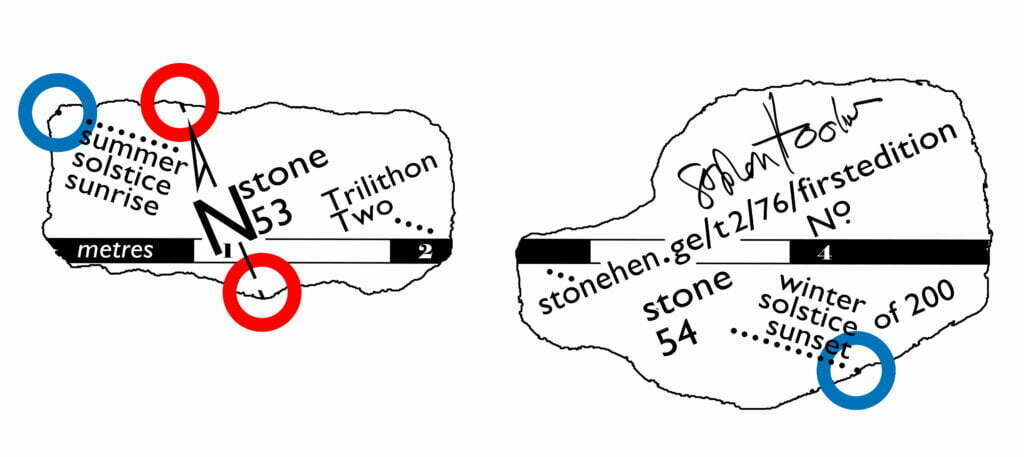

However, other and very rare axe and dagger carvings found around the UK are linked to funerary rituals. And the polished inner face of skinny Stone 53 point directly at the prominent burial mounds known as the Cursus Group. (However, tumuli are all over the place.)

All the axes and daggers around Stonehenge are life-sized so it’s thought that real axes were used as a stencil. But some around the stone circle are bigger than those already found throughout the UK. So perhaps these bigger ones were stenciled from ceremonial axes and daggers.

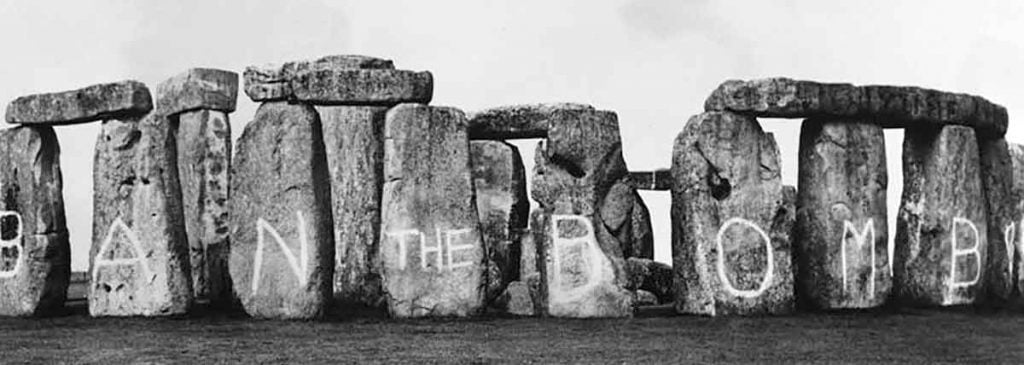

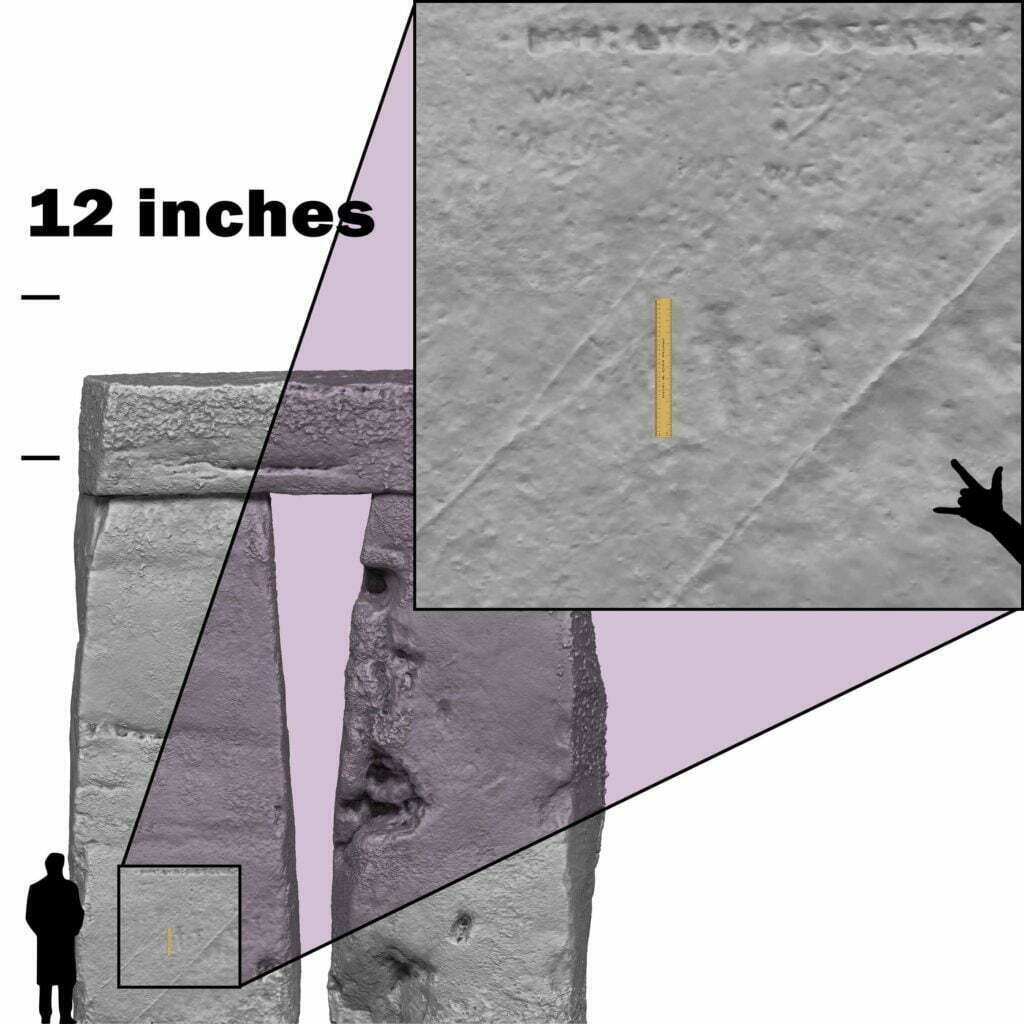

Graffiti

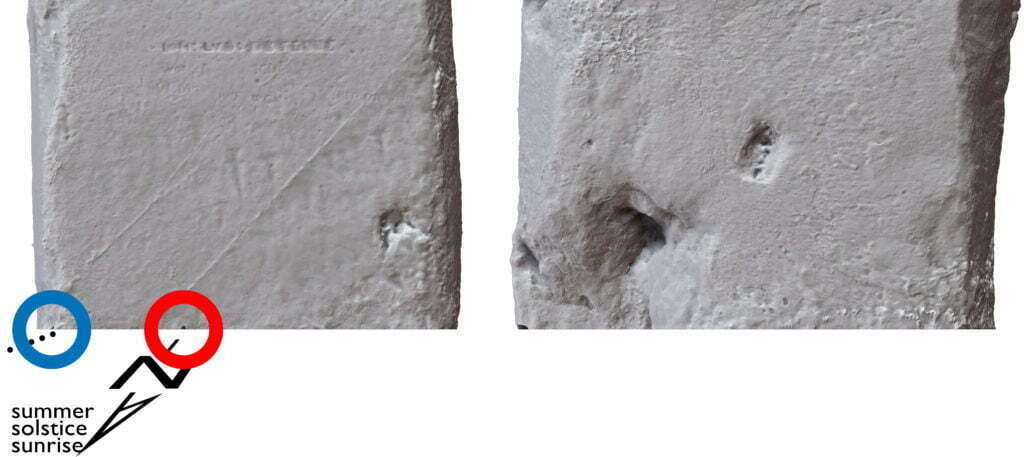

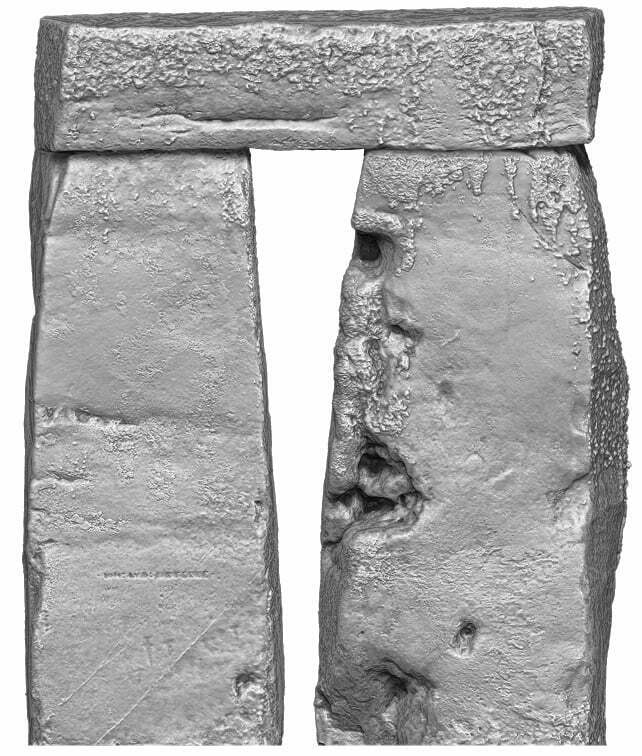

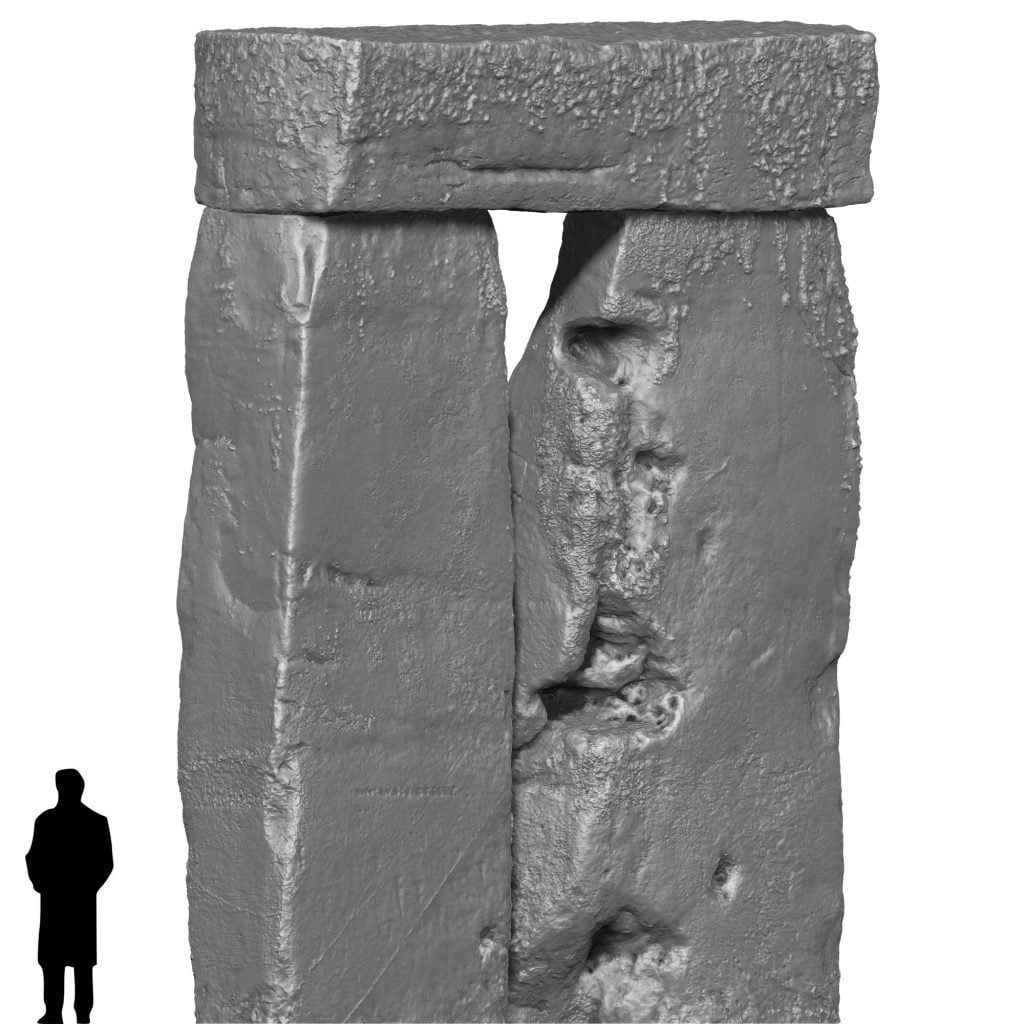

Examine the 17th-century graffiti on Stone 53.

IOH:LVD:D∑ F∑RR∑

It’s at eye-level – I’m 6′ 2″. Probably Johannes Ludovicus (or John Louis) de Ferre. In their report on the recent laser scanning for English Heritage, Anderson-Whymark and Abbott note a London poet called John Louis de Ferre who died in 1884, aged 83. The 17th-century lettering style and weathering means the carving certainly pre-dates the 19th century.

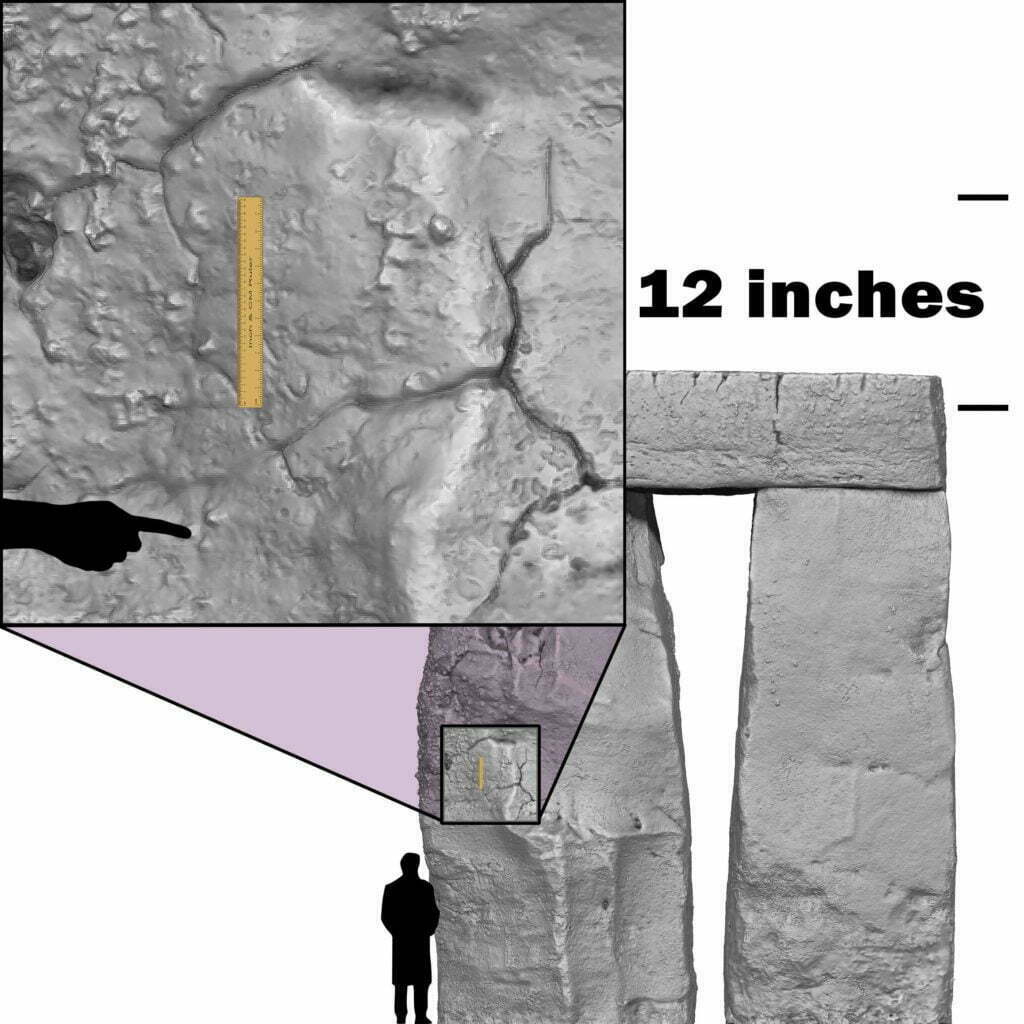

Hammerstone mauls

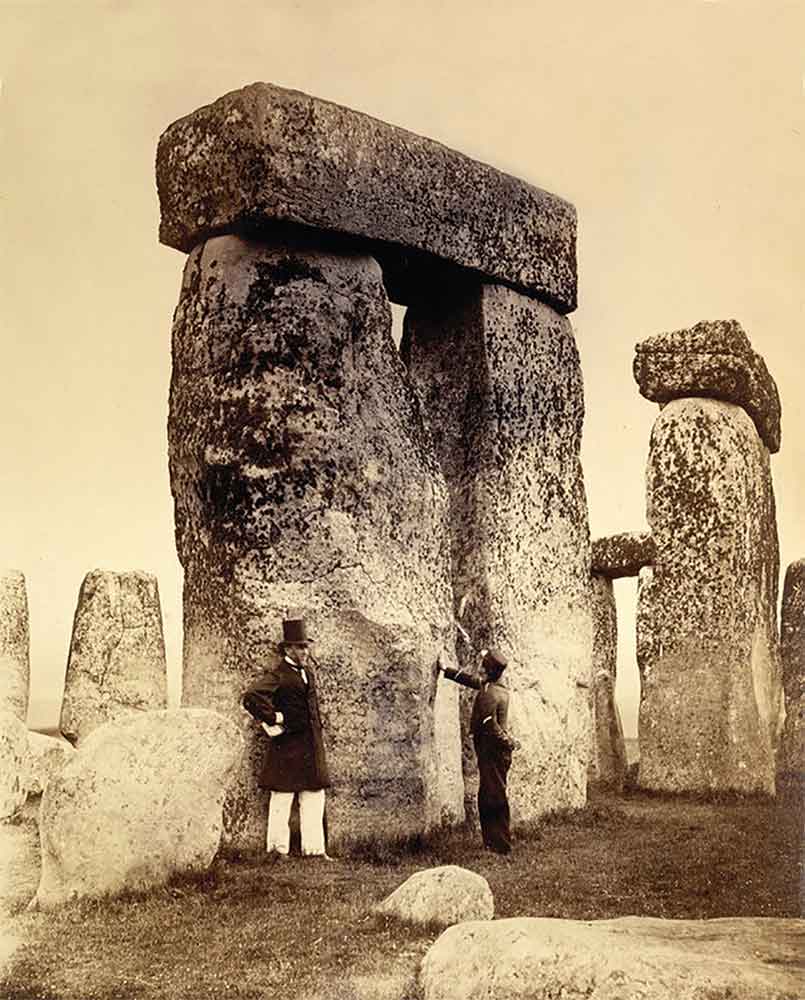

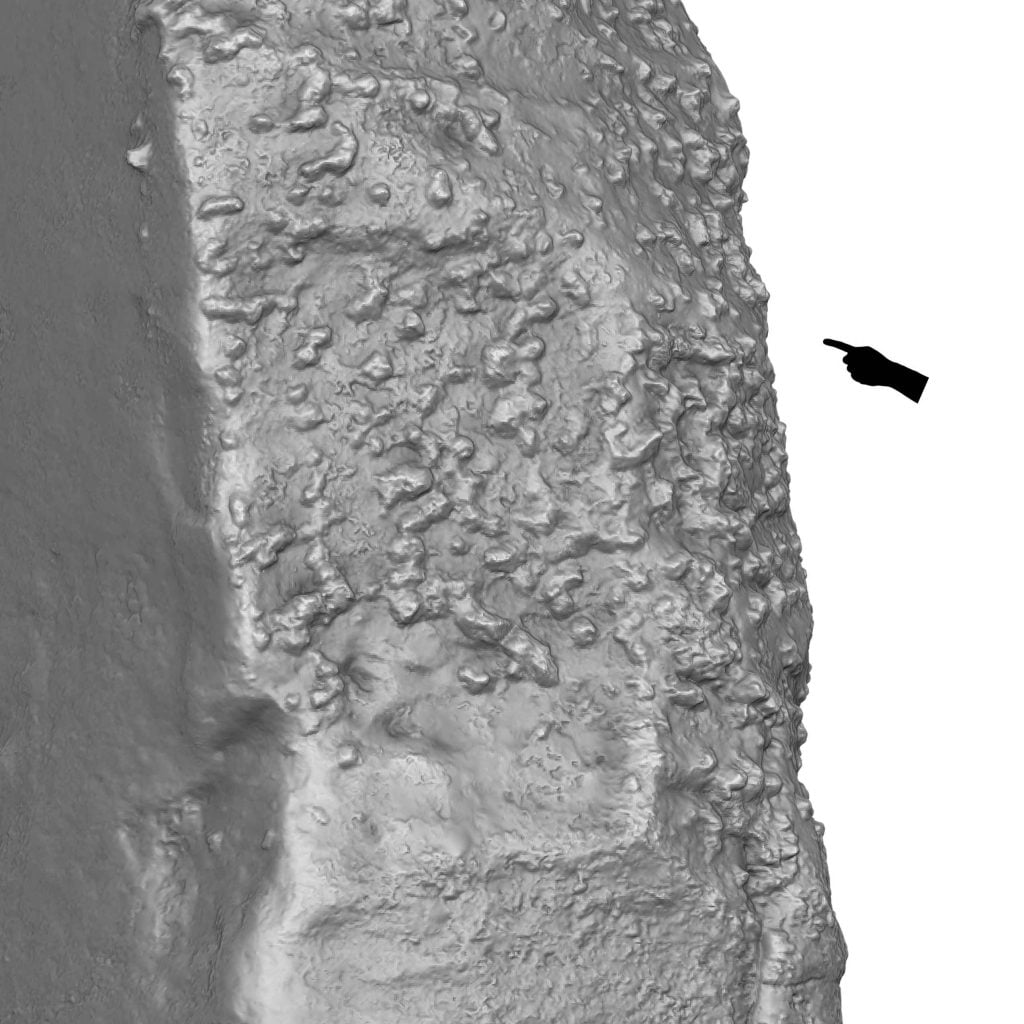

Carved to shape

Hammerstones were used to bash the rough sarsens to shape. The remains of this work is obvious when you know what to look for.

The longer upright ridges are roughly bashed first, then the smaller horizontal lines mostly 4-5 inches apart. Best seen on the exterior outside faces.

Now, sarsen is silicified sandstone. That’s quartz – it’s hard. So you’ll need to bash it with something as hard or harder. The hardest sarsen was used, some up to 7 pounds, others about a pound. The chippings are found all around Stonehenge, so that’s where the majority of the shaping happened. The mauls were reused as infilling and packing the base of the uprights as they were erected.

Deliberate shapes

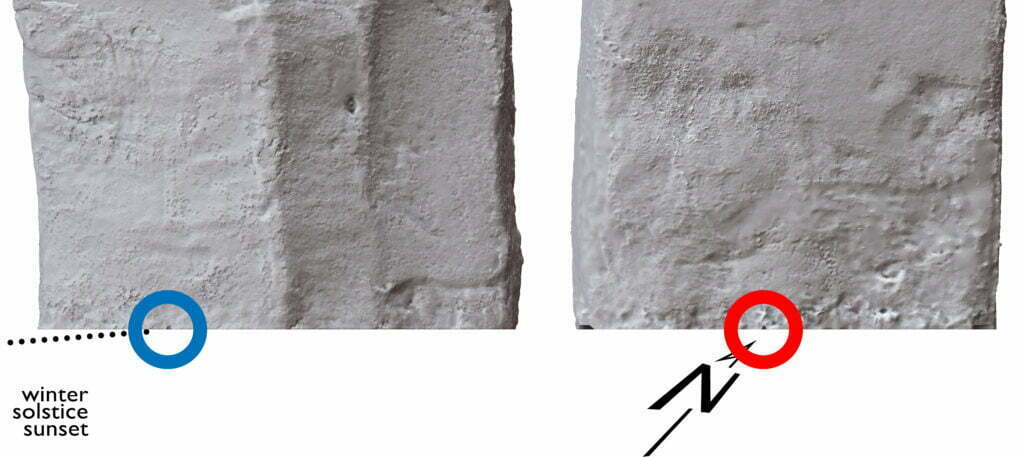

Smooth & polished inside

Speculate over the smooth interior faces of the uprights. Were they painted? It’s a lot of work to get them flat, but these are polished too. There are no ridges here.

Now, we know that the main view was from north-east down the processional Avenue, near the Heel Stone. Everything in that view pointing to the mid-winter sunrise is more finely worked. These finely polished surfaces would have been in that view although obliquely.

Experiments have demonstrated that it takes one man one hour to chip away 6 cubic inches (1.8″ x 1.8″ x 1.8″) and it’s speculated that there was 3,000,000 cubic inches to crunch away at Stonehenge, then that’s 57 man years, but they’d need some sleep, mead breaks and holidays at the beach, days off for bad weather and solstice celebrations – so 228 man years IMHO. More likely, and obviously, it would have taken 228 men people one year to smash those three million cubic inches. One should take into consideration that once the uprights were in place – the builders would have needed to leave them settle before placing the lintels on top. Maybe a year or more?

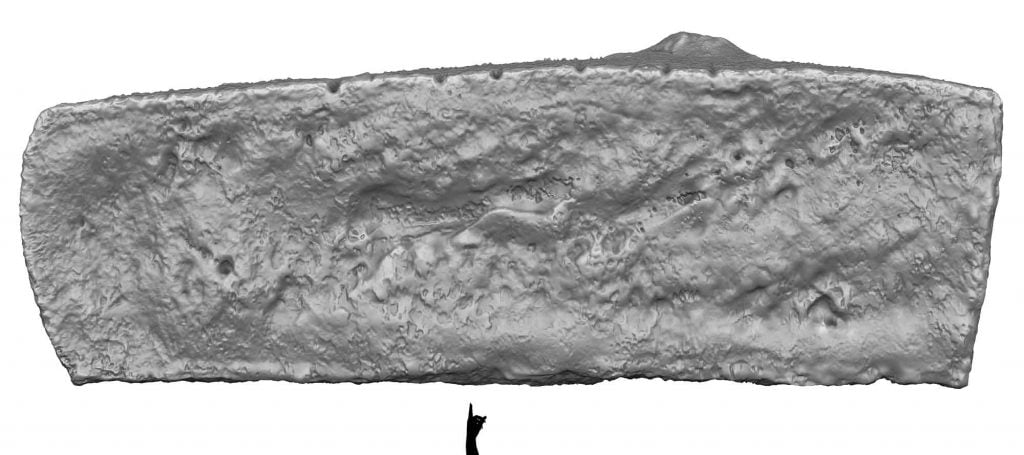

Cut here. No! Not there

Consider the finely worked edges of the lintel – Stone 154. Compare to Trilithon Four’s lintel – Stone 158, which lay on the floor for over 160 years – chipped away by souvenir hunters. This lintel isn’t square, man 😉 But it is straight. Though curved on the outside. And really curved on the short south-west face. It’s quite an odd shape. Out of all the shapes that could have been chosen…

The V shape between the stones must have great significance. I can’t squeeze through, I’ve seen women and children do it, I’m not too porky, given half an hour, maybe I could… Why such a fine measurement?

I’ve called them fatty and skinny – more memorable for me. We currently use impersonal numbers to identify the stones. The builders wouldn’t have. They’d have given them names. Perhaps personalities, mannerisms too. Perhaps they were actual gods or representations, icons of gods.

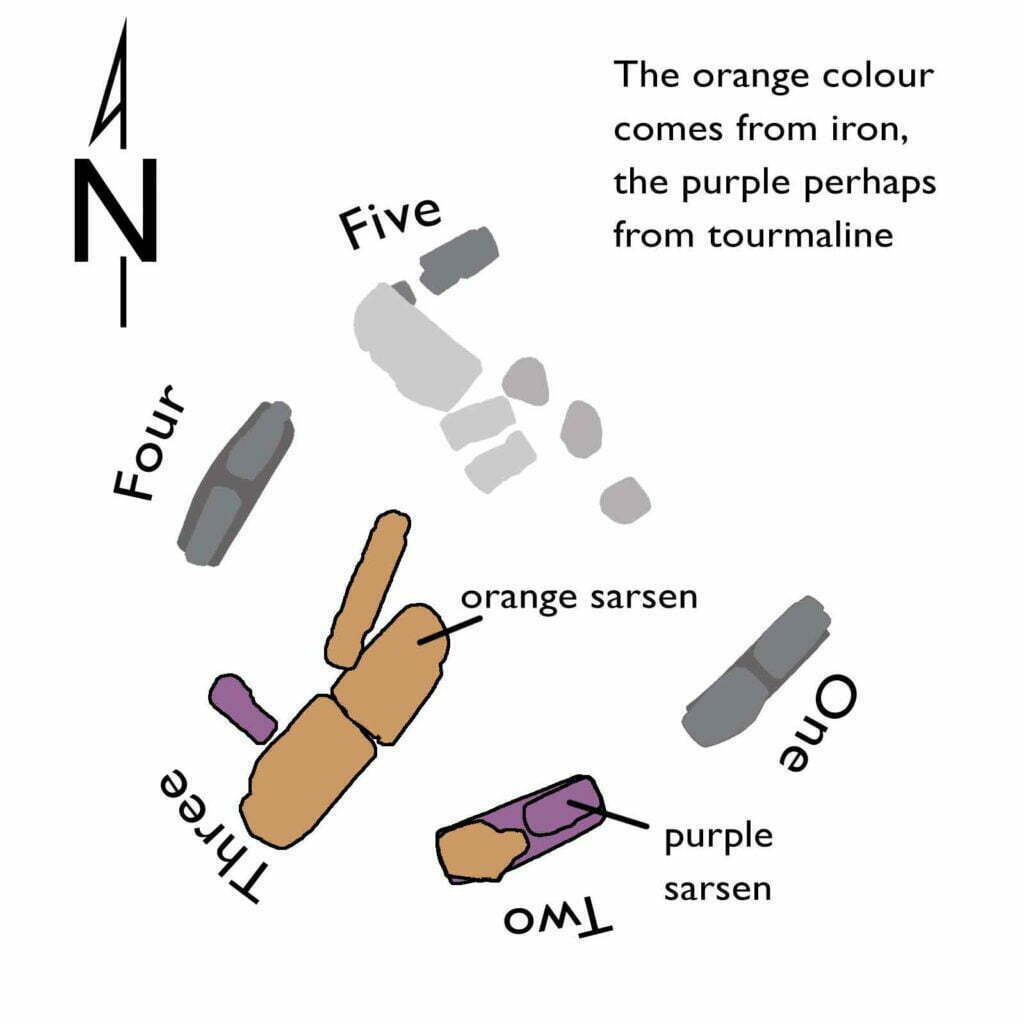

Each trilithon is the same, one rough and bulky, the other smoother and slimmer. And each trilithon is made up of two types of sarsen. Skinny Stone 53 and lintel Stone 154 are purple grey sarsen while fatty Stone 54 is orange sarsen. What’s that about?

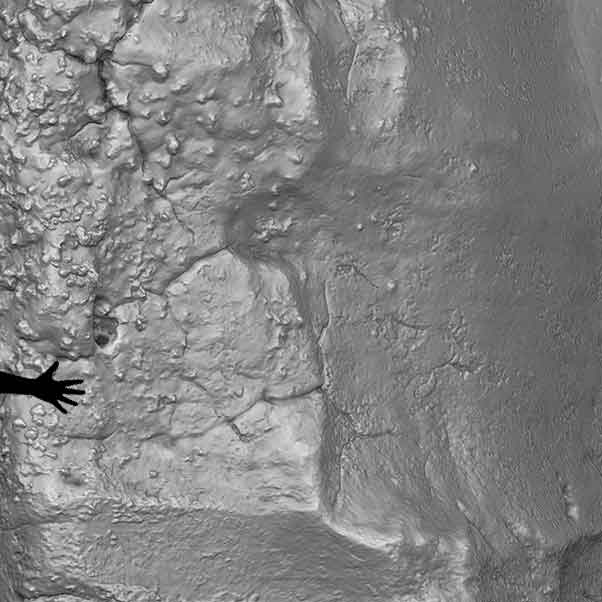

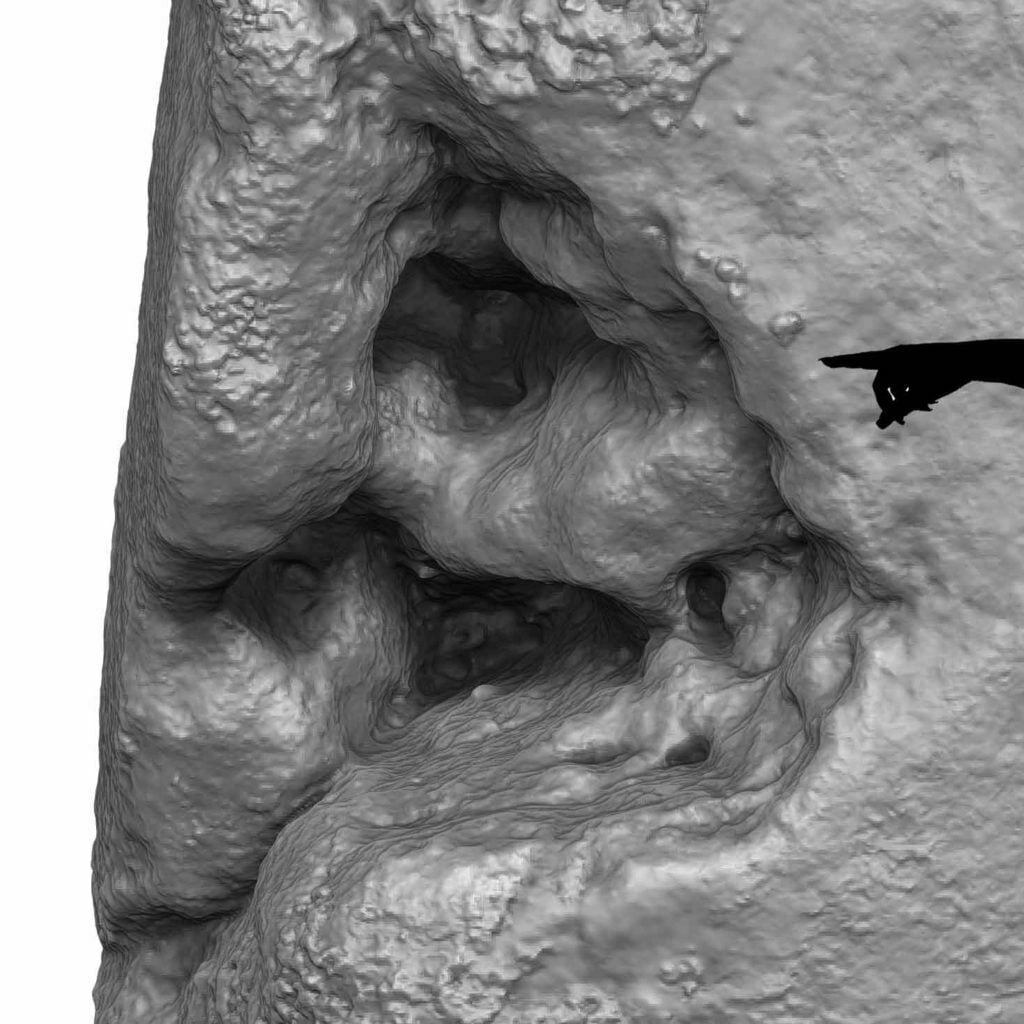

Sarsen’s hard and vuggy

And imperfect

Read lots more about Stonehenge sarsen – a type of sandstone.

Look at cracks and holes in the sarsen sandstone – weathering over 4,400 years after the builders’ hammerstone dressing. Were some of the imperfections present then? Sarsen is vuggy – look it up. It means riddled with small cavities or spaces – often lined with crystals.

Puzzle over what the builders would have thought about the flint pebbles called pudding stones embedded in the rock.

Or even fossil root holes probably from prehistoric palms – common in sarsen. What logic would they have attributed to this?

Sarsen sweats in damp weather, water condenses on them and makes them look like giant lumps of coarse sugar. Like they were living.

Sarsen sweats in damp weather. What would the builders of Stonehenge thought about that? Share on XAnd over millennia sarsen boulders slip down dry valleys collecting in ‘sarsen trains.’ The builders would have marveled at these collections strewn across valley floors.

Reconstruction or repair?

We will fix it, fix it

Look at the repaired angles. Eyeball that wonky vertical! It was dangerously worse but corrected in 1964 when Stone 54 and Stone 53 were embedded in concrete – lintel Stone 154 had to be temporarily lifted for the fix. There have been extensive repairs to a lot of stones at Stonehenge during 1901, 1919, 1920, 1958, 1959 as well as 1964.

“The Committee…recommended to Sir Edmund Antrobus the making safe of one of the trilithons which was gradually twisting round to such an extent that the capstone would eventually fall.

From Historic England’s research report ‘Restoring’ Stonehenge 1881-1939

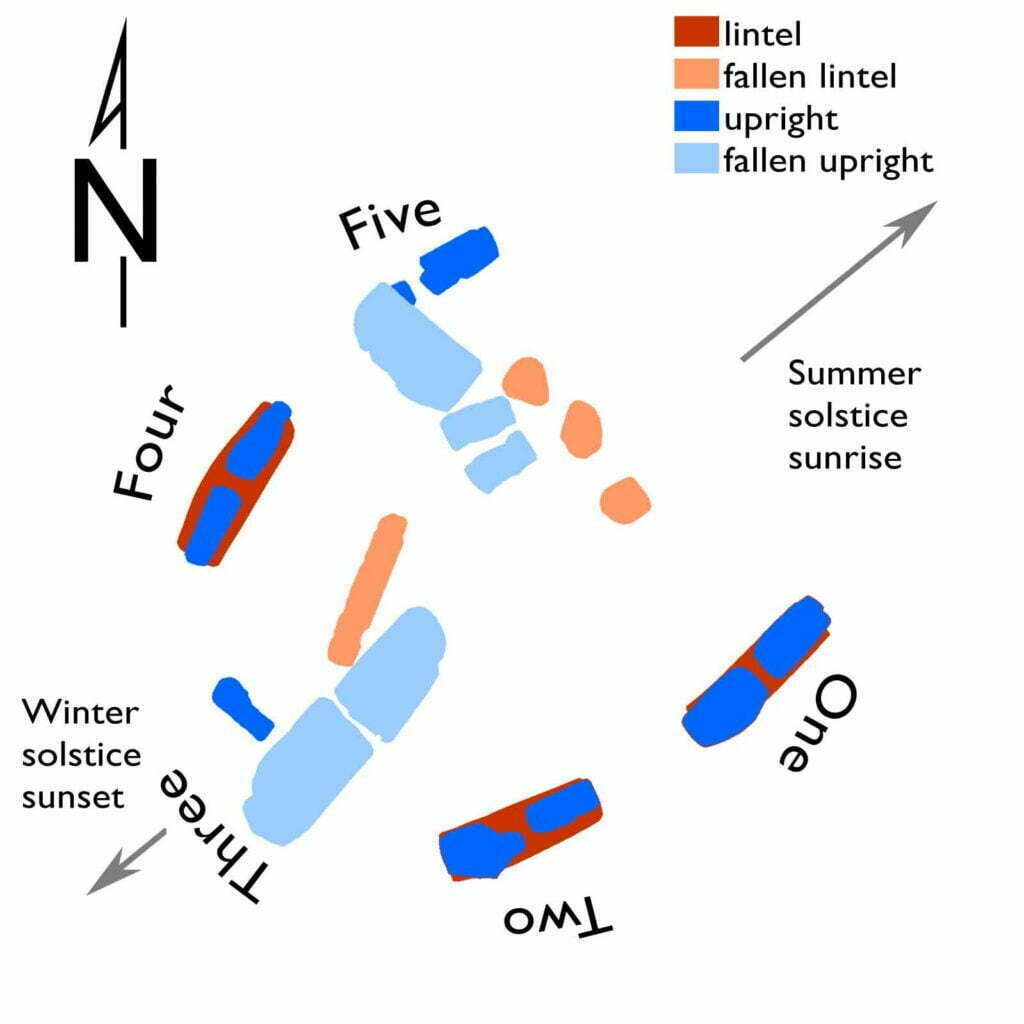

Sophisticated stone age mathematicians

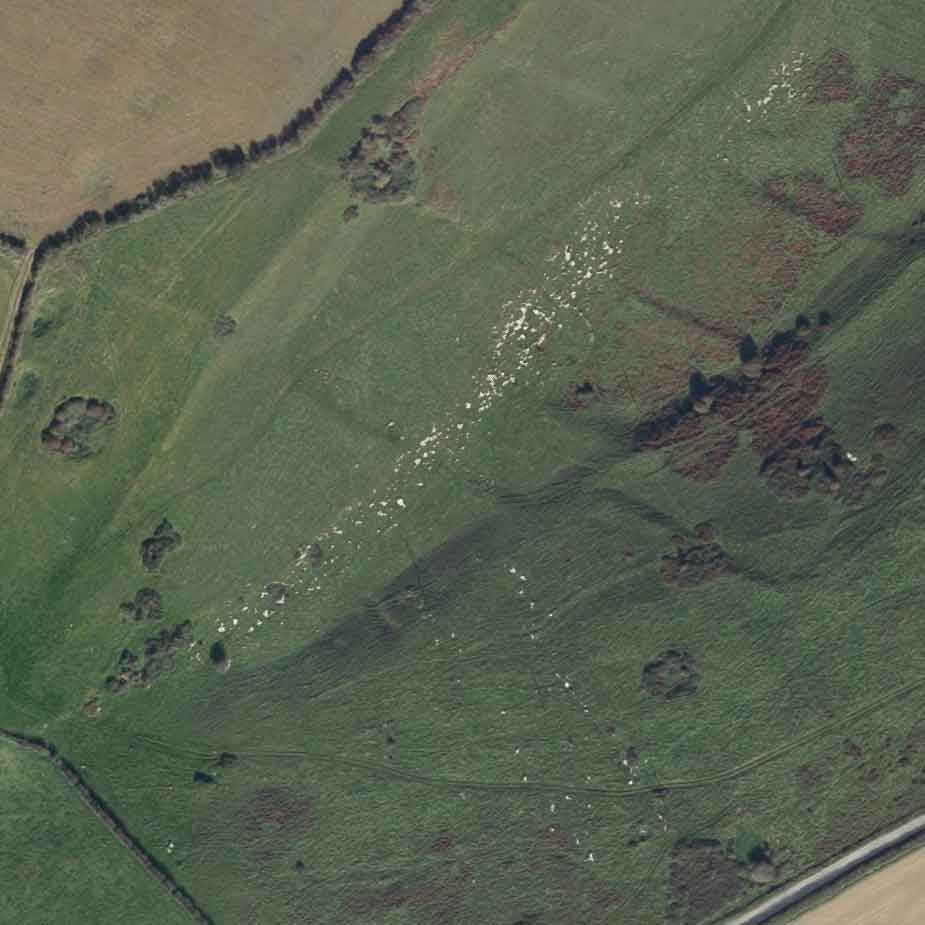

Was Stonehenge an astronomical clock Share on XThe builders had a purpose. Was it an astronomical clock, for predicting the heavenly bodies or for calculating the seasons? The winter solstice sunset seems to be the main gig. With the sun setting in the south-west.

Standing on the Avenue looking between the Heel Stone (Stone 96) and its missing partner you’d see the winter sun setting between Stone 1 and Stone 30 on the outer sarsen circle, just over the recumbent Altar Stone (Stone 80) and between the uprights of the Great Trilithon, through to the opposite outer sarsen circle, Stone 16 and moved Stone 15. All the faces to the stones are finely dressed and some polished for this view.

Or was it all for the other way – the opposite summer solstice sunrise? When the shadow of the phallic Heel Stone enters the female monument?

But the trees on Larkhill ridge have raised the horizon to move the sunrise to the right of the top of the Heel stone.

Predict the rise and fall of the stock market using Stonehenge Tell a friendUsing the notches align them with the north, and they’ll be aligned with the solstices. Amaze your friends by being able to predict the moon’s journey. The passage of planets. And the rise and fall of the stock market.

Conundrums, riddles, puzzles, secrets?

Why? Why? Why?

There are always ‘new revelations and discoveries’ that are to ‘rewrite the history of Stonehenge.’ Now, we can join in, too and figure out why.

- Why do the great trilithons increase in height?

- Why are the uprights in T1 very stocky while in T4 they are thin? And T2, T3 and T5 have both stocky and slim uprights?

- Why are the inside faces of the trilithons and some of the outer circle polished? Yet the outside of The Great Trilithon is also finely dressed

- Why did the builders mix up grey and orange sarsen?

- Why are the gaps between the uprights barely wide enough for a grown person to squeeze through?

- And the four lesser great trilithon’s gaps a pronounced V while the main Great Trilithon’s gap is straight?

- Why did they leave those long vertical marks on the back of some of the trilithons?

- Why did they carve those axes and daggers?

- And why only in groups on certain stones – S53 particularly?

- Why did they cut the lintel straight on the inside edge yet curved on the outside?

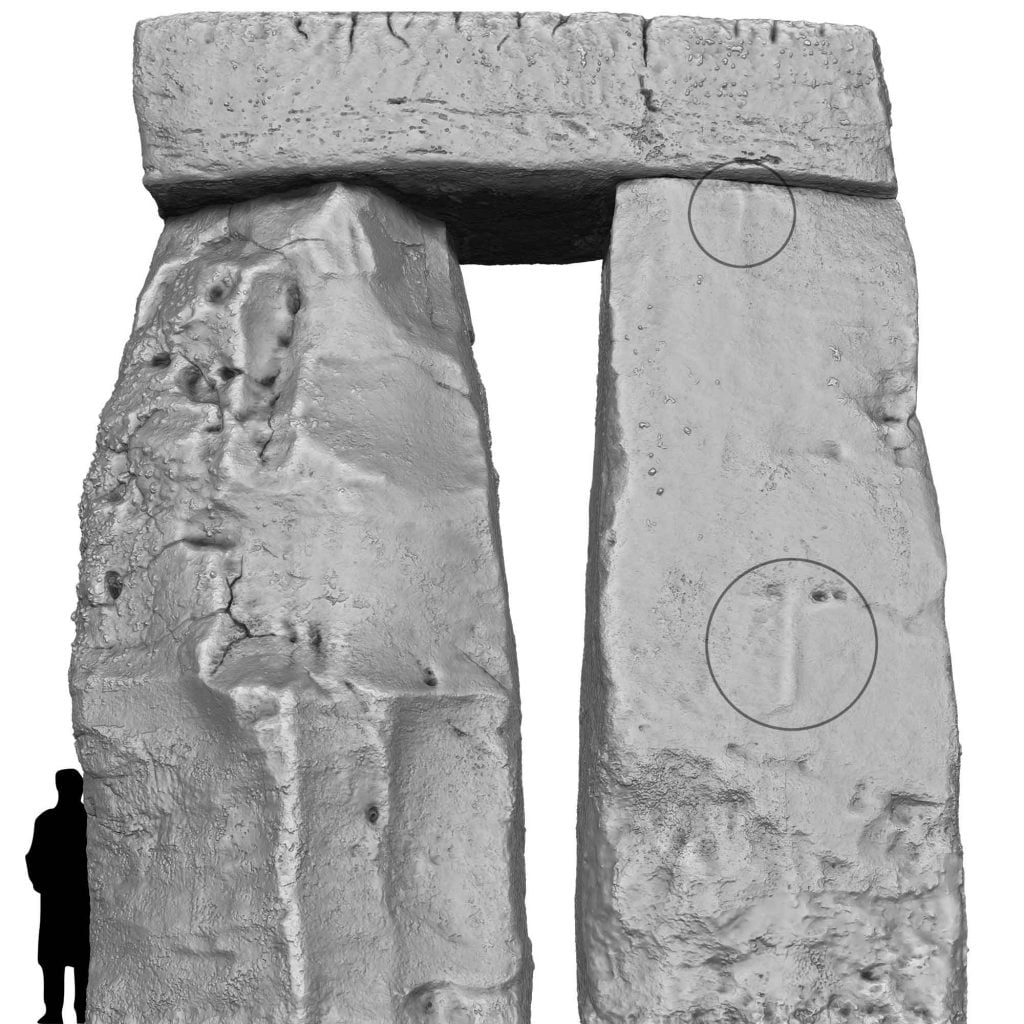

The man in the moon

The face

The word of the day for you perhaps, for me as a witch photographer I get it all the time with my pictures, people see things I didn’t do! The word is pareidolia – when you see something that’s not there. We have one where I live: the face of Abraham Derby, the builder of The World’s First Ironbridge. Started donkey years ago. Now there are more faces than you can shake a stick at.

It is the first face ever seen on the Neolithic monument and one of the oldest works of art ever found in Britain.

It was recognised by Terrence Meaden, an archaeologist with a fascination for the ancient standing stones of the British Isles.

“I just happened to be there at the right time of day because only when the light is right can you see it properly. During the summer months, it is only obvious for about an hour each day around 1400.”

Quoted from the BBC’s Sci/Tech site. And the good Doctor’s page about it.

Ogham runes

On the delicious Megalithic site a discussion ensued over characters carved on the stones.